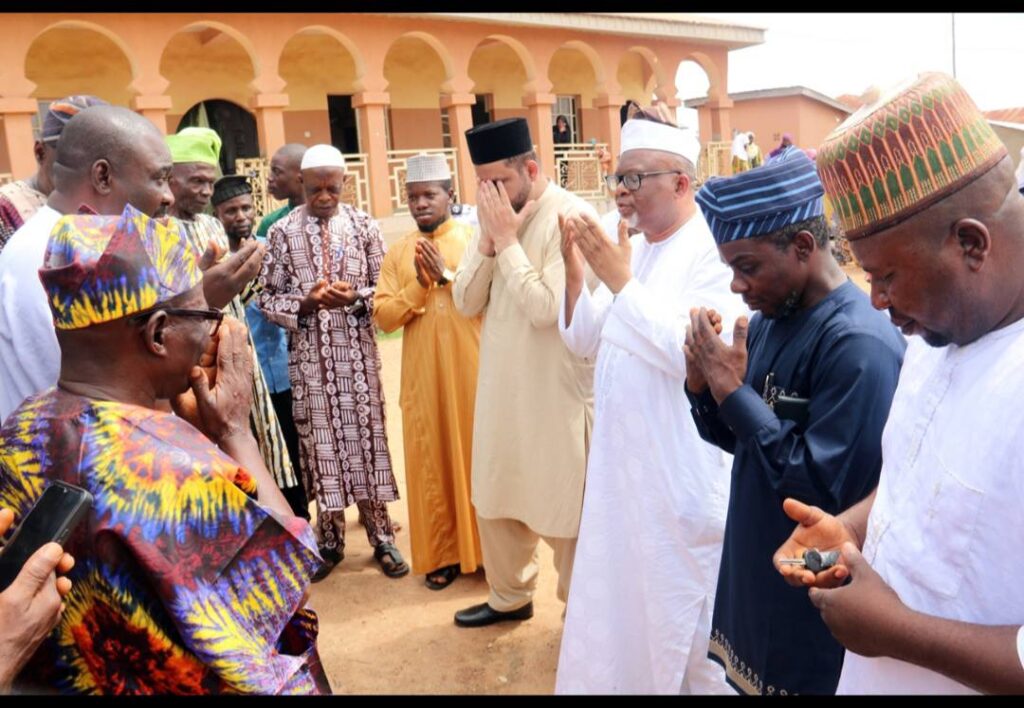

The Amir (National Head) of Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at of Nigeria Respected Alhaj (Barr.) Alatoye Folorunso Azeez, on Friday 11th July 2025, paid official visit to the New Grand Khadi of Kwara State Shariah Court of Appeal, Honorable Justice Abdul Lateef Kamaldeen Al-Adaby in Ilorin Kwara State. The purpose of the visit was to pay homage to the new Grand Khadi being the tradition of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community to foster healthy relationships with top government officials, first-class traditional rulers, and highly placed dignitaries. The august visit is also in continuation of the long standing relationships with the former Grand Khadis in Kwara State, the recent being Retd. Justice S.O Muhammad. The Amir sahib appreciated the efforts of the Grand Khadi on the successful administration of the Sharia Court. His tenacity and sagacity towards upholding the rule of law without any compromise were also commended. The Amir further called for unity of faith among Muslim faithful against common enemies. He enjoined Muslim Ummah to emulate the life styles of the Holy Prophet whose leadership prowess tempted his companions to stand up against the enemies of Islam. In his words: “The leadership and followers of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Nigeria humbly use this opportunity to congratulate you on your appointment as the new Grand Khadi for Kwara State. We appreciate you for granting us the courtesy visit out of your tight schedule. “It is important to reiterate again that Islam is a religion of peace void of any form of violence nor act of terrorism. Those who are using the religion to forment troubles are doing so out of ignorance and selfish interest such as resource control, territorial acquisition and power acquisition.” “It is thus incumbent on all Muslims across the globe to unite as one family and challenge the common enemies of Islam. This is because The supremacy of Islam over other religions should not be contestants. All Muslims should believe in the existence and oneness of Almighty God.” The National Head also corrected some of the misconceptions about Ahmadiyya Muslim Community with respect to five pillars of Islam and the seal of the prophets. He said: “Obviously there were some misconceptions about Ahmadiyya Community. Some believed Ahmadis don’t perform Hajj and that Ahmadis has their Holy Quran apart from the one revealed to the Holy Prophet Muhammad (Saw). I wish to inform you that they are all false accusations. We believe and practice all the five pillars of Islam., pilgrimage to Mecca inclusive. We believe in the unity of Allah and the Holy Prophet as a great exemplar in Islam. We also subscribe to the notion that the Holy Prophet is the seal of all prophets and best of mankind.” “The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community project the image of the Holy Prophet throughout the world. The Holy Qur’an is unique and can never be replicated. How on earth can we then have our own Qur’an,” Barr. Alatoye queried. He continued: “The coming of the Promised Messiah (AS) should not cause any enmity or hatred among us. The Holy Quran and Sunnah of the Holy Prophet are there for us as vital tools of guidance and direction.” “Ahmadis globally are known for preaching oneness of Allah, unity of Islam and peaceful co-existence. These are the preachings of the worldwide head of Ahmadiyya Community, as he continues to address world leaders on the need to embrace peaceful co-existence and avert World War 3.” ” The Jama’at is also known for providing humanitarian services to the needy, homeless and the less privileged across the world. In Nigeria, Ahmadiyya Community pioneered the Western Education combined with Islam to Muslim children through the building of schools across the country. Hon. Justice Abdul-Lateef Kamaldeen informed that he was well aware of all the numerous and landmark achievements of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community across the world, and therefore labeled the Jama’at as a “Pillar of Peace”. He noted that the meeting has corrected numerous wrong impressions about the Community. He thus urged the Jamaat leadership to always create avenues to enlighten other Muslims about the activities of the Jamaat. Among the entourage of the Amir are: Naib Amir Finance and Administration, Alh. Mufadhil Bankole; Naib Amir Tabligh and Tajneed, Dr. Abdul-Lateef Busari; National General Secretary Alh. Abdul Jabar Ayelagbe; former Amir AMJN and National External Affairs Secretary Prof. Mashhud Fashola, among others.The Amir (National Head) of Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at of Nigeria Respected Alhaj (Barr.) Alatoye Folorunso Azeez, on Friday 11th July 2025, paid official visit to the New Grand Khadi of Kwara State Shariah Court of Appeal, Honorable Justice Abdul Lateef Kamaldeen Al-Adaby in Ilorin Kwara State. The purpose of the visit was to pay homage to the new Grand Khadi being the tradition of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community to foster healthy relationships with top government officials, first-class traditional rulers, and highly placed dignitaries. The august visit is also in continuation of the long standing relationships with the former Grand Khadis in Kwara State, the recent being Retd. Justice S.O Muhammad. The Amir sahib appreciated the efforts of the Grand Khadi on the successful administration of the Sharia Court. His tenacity and sagacity towards upholding the rule of law without any compromise were also commended. The Amir further called for unity of faith among Muslim faithful against common enemies. He enjoined Muslim Ummah to emulate the life styles of the Holy Prophet whose leadership prowess tempted his companions to stand up against the enemies of Islam. In his words: “The leadership and followers of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Nigeria humbly use this opportunity to congratulate you on your appointment as the new Grand Khadi for Kwara State. We appreciate you for granting us the courtesy visit out of your tight schedule. “It is important to reiterate again that Islam is a religion of peace void of any form of violence nor act of terrorism. Those who are using the religion to forment troubles are doing so out of ignorance and selfish interest such as resource control, territorial acquisition and power